Art has always been a mirror for reflecting society. Even ancient cave paintings depicted their artists' civilisations warts and all; you could maybe even say Egyptian hieroglyphics also did. Today, even very casual consumers of art have become accustomed to that. But many of us, I think, have lost faith in art's ability to make change or increase awareness of a cause. If not that, then no fewer of us have learned to smell overkill when we experience it.

In each art form, artists should be free to explore whatever themes or issues they choose, but if those are topical or confronting, how you approach them can mean the difference between moving the audience and smashing them over their heads with it. For cinema the most recent example I can think of that I found excessive was 2012's The Impossible, about a family on holiday in Bali when the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami hits. I found it so heavy-handed and unrestrained thanks to the score alone that I thought it should've been called The Unwatchable. There are plenty more films like that for me (including nearly all of Ron Howard's filmography, quite honestly), but that's the freshest in my mind. (And indeed I wish I could erase it from there.) Even worse was 2016's Deepwater Horizon, one of the most shamelessly ignorant and parochial films I have ever seen. For a recent, similarly dramatic movie that has the opposite effect, try 2013's devastating documentary Blackfish, which I've already reviewed here. That works so well because it was pointed but objective and balanced.

You can also do justice to delicate subject matter through metaphor. The Cranberries' 1994 hit song Zombie was long taken to be about, well, a zombie, but that imagery and title was actually meant to represent two children who were killed in an IRA terrorist bombing. The song is a passionately angry memorial to them and all the other casualties of Ireland's Troubles, and it's lost none of its relevance or power today. Looking at more intimately personal subjects, Lt. Col. Mark M. Weber's 2012 memoir Tell My Sons is a series of letters he wrote to his three young sons after being diagnosed with terminal intestinal cancer; no other book has ever made me cry. For a terrific novel about cancer, there's John Green's 2012 effort The Fault in Our Stars; its 2014 film adaptation is inferior but nonetheless worth watching, too, and Jodi Picoult's 2010 novel House Rules evokes the hardships of growing up autistic superbly (and having done that I should know). These four works, along with those of Lisa Genova (2009's Still Alice et al), are ideal examples of how to examine disease and disability in literature with restraint for more impact. Contrast that with anything by Nicholas Sparks, whose writing is notoriously manipulative.

Using art to tackle challenging subjects is always brave and well-intentioned, and I acknowledge all artists have their own styles, instincts and preferences. But for your work to generate empathy, thought, discussion or above all change, the key is not the subjects you cover but how you cover them.

Friday, 27 July 2018

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #96: Norman (2010).

High school senior Norman Long (Dan Byrd) is basically having a premature quarter-life crisis. Beyond being practically invisible at school, particularly with the girls, he's already overcoming the hurt from his mother Marie's death when his father Doug (Richard Jenkins) contracts terminal cancer. It's totally understandable, then, that he's developed a very twisted, cynical sense of humour. Pretty soon, his social standing school improves, but for a pretty awful reason. While trying to express the cause of his stress to classmate James (Bradley Cooper doppelganger Billy Lush), Norman has a communication breakdown and says he's the dying one. Naturally this fake news now spreads around school like the flu, and girls show a newfound interest in him and bullies try to make amends for past misdeeds. But Norman instead falls for a new girl in his drama class, Emily Parrish (Emily Van Camp), who dismantles all his barriers. Now, with help from Emily and his English teacher Mr. Angelo (Adam Goldberg), Norman must set the record straight.

Norman, I think, is easily one of the best and freshest coming-of-age flicks in recent years. Working from Talton Wingate's understated screenplay, Jonathan Segal invokes an appropriately homely visual language to flesh the essence of its character dynamics right out: Norman and Doug, Norman and Emily and school Norman and home Norman. It's a wise technique that achieves a very sincere and dignified result, and enhancing this is Andrew Bird's score and Darren Genet's photography.

And anchoring it are four solid central performances. Dan Byrd (who you might know from Heroes, Cougar Town and as Emma Stone's gay "boyfriend"in Easy A) gives his finest, hardest turn to date as this boy whose passage into adulthood is proving hardly auspicious; he makes every emotion seem authentic, particularly as the film approaches its emotional climax. Van Camp takes what could've been just another passive, sickly-sweet girlfriend role and brings true backbone to her, Jenkins's quiet and weathered authority has seldom been employed better and also in a fairly trope-ish role, Goldberg is well-balanced.

It falls short of many similar earlier flicks, but Norman stands out because it dares to aim for the big emotional gut-punches, and knows how they should be thrown. Subsequently, I ultimately find it also quite thought-provoking. These questions may be unpleasant or unpopular, but illness and death in one's family can change us irrevocably, especially if they strike suddenly and while we're growing up. Norman offers a beautifully delicate look into navigating that precarious terrain.

It falls short of many similar earlier flicks, but Norman stands out because it dares to aim for the big emotional gut-punches, and knows how they should be thrown. Subsequently, I ultimately find it also quite thought-provoking. These questions may be unpleasant or unpopular, but illness and death in one's family can change us irrevocably, especially if they strike suddenly and while we're growing up. Norman offers a beautifully delicate look into navigating that precarious terrain.

Thursday, 19 July 2018

The Wild Boars in the cave.

It might be this year's biggest worldwide news story: the teenage Wild Boars soccer team and their coach trapped for nine days in a cave in Thailand after a flood. Now they're thankfully out and reunited with their families, but the media's still not letting it go. And just to get it out of my system, I imagine playing I Spy must've lost its novelty pretty soon in there ("I spy with my little eye, something beginning with... C!"). They're the Chilean miners of 2018.

As you probably know, they also had to be freed individually, and not starting with the youngest or weakest. But while they may be out and physically recovering, I'm sure they have quite a road yet, as anybody else would, to mental and emotional recovery; the media would do well to consider this. Stuck in such cold, wet and dark conditions unexpectedly, for that long and at that age (besides the coach) and then to finally escape only to encounter reporters from across the world and the insatiable clicking of their cameras and questions with their microphones. Compounding this, I also wonder how they must've reacted to the news of navy SEAL Saman Gunan's drowning death as he tried to rescue them. In their position I'd be stunned that I survived and he didn't. Regardless, it's now been claimed several of the boys want to be navy SEALs as a tribute to him, and I salute that.

I was gut-wrenched last week to read of Hollywood producers appearing on the site, before the rescue had even been completed, to enquire about rights to a film of the tale. That's the greediest, most opportunistic thing I've heard in ages, but it should not distract from the media squeezing this story like a watery sponge. The team and their coach all surviving physically should be celebrated, but now let's just let them all mentally recover privately as they return to their lives as they knew them.

As you probably know, they also had to be freed individually, and not starting with the youngest or weakest. But while they may be out and physically recovering, I'm sure they have quite a road yet, as anybody else would, to mental and emotional recovery; the media would do well to consider this. Stuck in such cold, wet and dark conditions unexpectedly, for that long and at that age (besides the coach) and then to finally escape only to encounter reporters from across the world and the insatiable clicking of their cameras and questions with their microphones. Compounding this, I also wonder how they must've reacted to the news of navy SEAL Saman Gunan's drowning death as he tried to rescue them. In their position I'd be stunned that I survived and he didn't. Regardless, it's now been claimed several of the boys want to be navy SEALs as a tribute to him, and I salute that.

I was gut-wrenched last week to read of Hollywood producers appearing on the site, before the rescue had even been completed, to enquire about rights to a film of the tale. That's the greediest, most opportunistic thing I've heard in ages, but it should not distract from the media squeezing this story like a watery sponge. The team and their coach all surviving physically should be celebrated, but now let's just let them all mentally recover privately as they return to their lives as they knew them.

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #95: Galaxy Quest (1999).

For four years, the intrepid crew of the NSEA Protector left Earth for thrilling and dangerous outer-space missions... before their series was axed. Now, twenty years later, the cast of Galaxy Quest - Jason Nesmith aka Captain Peter Quincy Taggart (Tim Allen), Gwen DeMarco aka Lieutenant Tawny Madison (Sigourney Weaver), Alexander Dane aka Dr. Lazarus (Alan Rickman), Tommy Webber aka Laredo (Daryl Mitchell) and Fred Kwan aka Tech Sgt. Chen (Tony Shalhoub) - are getting by only on a carousel of monotonous science fiction conventions where their fans are as obsessed as possible. At one convention, though, they also meet a group aliens known as Thermians and their leader Mathazar (Enrico Colantoni), who've intercepted the broadcasts of Galaxy Quest as "historical documents" and are currently under attack from the evil Sarris (Robin Sachs) and his crew. After they are then reluctantly beamed up into space to help the Thermians, with no script, director or clue the washed-up actors, along with apprehensive convention host Guy Fleegman (Sam Rockwell), must give the performances of their lives in order to save the universe for real this time.

Galaxy Quest is like the ultimate go-to source for how to achieve both a sharp parody of and loving homage to something (in this case Star Trek). Director Dean Parisot and writers Robert Gordon and David Howard most immediately get us acquainted with this ragtag team of quarrelling actors and their TV alter-egos torn straight from Gene Roddenberry's creations, and give them realistic dynamics and struggles: Gwen and particularly Alexander are sick of their characters (reminiscent of how Leonard Nimoy often found himself trapped in his Spock character), and the others all hate the egotistical Jason. Parisot, Gordon and Howard also do a very knowing job of depicting SF fans and how for many of us, it's way more than just a genre. It's something that really nourishes and unifies us; a great help in driving this message home is the subplot with nerdy teenage fanboy Brandon (Justin Long), who helps the crew after meeting Jason at the convention. There's also solid visual effects, a suitably serial-esque score and rich make-up by the late, great Stan Winston to be savoured here.

The stars are all on top form, too. Former animated space cowboy doll Allen channels William Shatner/James T. Kirk to just the right pitch, Weaver (my eternal Queen of Science Fiction) revels in playing a comic twist on her iconic Ellen Ripley role, Rickman effortlessly lets his browbeaten character's anger and sadness seep out gradually for more impact, Shalhoub (aka Jeebs, the alien whose head grew back in Men in Black) has many of the wittiest lines and scores with them all, and Colantoni and Missi Pyle (as the main female Thermian, who can't talk) are respectively touching and blisteringly funny. But for me the MVP here is Sam Rockwell, who had arguably the hardest role because it was the most original, and yet he so memorably creates this increasingly nervous wingman that he will leave you in fits of laughter, especially in the priceless climax.

It's thoroughly satirical and irreverent, but also sincerely affectionate and touching as an examination of science fiction and its fandom. Galaxy Quest is unquestionably one of the best parody movies ever made, and a well-deserved cult classic.

Galaxy Quest is like the ultimate go-to source for how to achieve both a sharp parody of and loving homage to something (in this case Star Trek). Director Dean Parisot and writers Robert Gordon and David Howard most immediately get us acquainted with this ragtag team of quarrelling actors and their TV alter-egos torn straight from Gene Roddenberry's creations, and give them realistic dynamics and struggles: Gwen and particularly Alexander are sick of their characters (reminiscent of how Leonard Nimoy often found himself trapped in his Spock character), and the others all hate the egotistical Jason. Parisot, Gordon and Howard also do a very knowing job of depicting SF fans and how for many of us, it's way more than just a genre. It's something that really nourishes and unifies us; a great help in driving this message home is the subplot with nerdy teenage fanboy Brandon (Justin Long), who helps the crew after meeting Jason at the convention. There's also solid visual effects, a suitably serial-esque score and rich make-up by the late, great Stan Winston to be savoured here.

The stars are all on top form, too. Former animated space cowboy doll Allen channels William Shatner/James T. Kirk to just the right pitch, Weaver (my eternal Queen of Science Fiction) revels in playing a comic twist on her iconic Ellen Ripley role, Rickman effortlessly lets his browbeaten character's anger and sadness seep out gradually for more impact, Shalhoub (aka Jeebs, the alien whose head grew back in Men in Black) has many of the wittiest lines and scores with them all, and Colantoni and Missi Pyle (as the main female Thermian, who can't talk) are respectively touching and blisteringly funny. But for me the MVP here is Sam Rockwell, who had arguably the hardest role because it was the most original, and yet he so memorably creates this increasingly nervous wingman that he will leave you in fits of laughter, especially in the priceless climax.

It's thoroughly satirical and irreverent, but also sincerely affectionate and touching as an examination of science fiction and its fandom. Galaxy Quest is unquestionably one of the best parody movies ever made, and a well-deserved cult classic.

Saturday, 7 July 2018

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #94: American History X (1998).

Teenaged Danny Vinyard (Edward Furlong) has to write a report for his high school history class on book reflecting historical human rights, and knowing his teacher Mr. Murray (Elliott Gould) is Jewish, Danny chooses Mein Kampf. Naturally this nearly gets him expelled until the black principal Bob Sweeney (Avery Brooks) decides instead to give Danny a course called "American History X," his first assignment for which involves his elder brother Derek (Edward Norton). Several years earlier, black drug dealers murdered the boys' father and during a TV news interview immediately thereafter, Derek launched into a racist tirade. Derek then teamed up with local nonfiction author Cameron Alexander (Stacy Keach) to head an active branch of neo-Nazi skinheads and after killing two black teenagers who tried to steal his truck, Derek was sent to prison where he's now served three years. He's now made parole, and Danny, his girlfriend Stacey (Fairuza Balk) and former gang-members can't wait to see him again. But after all his prison experiences, and unexpectedly making friends in there with a black inmate (Guy Torry) he was assigned to partner with for work detail, Derek is unequivocally changed. Ashamed of his past, Derek must now race to save his family from the legacy of his crimes.

American History X is such an unflinching and authentic sociological cautionary tale that you may have to be in the right mood for it, but when you are it will be well worth it. Englishman (and rather fittingly a Jew) Tony Kaye, although he disowned the final cut after New Line Cinema and Norton (whom he clashed with during filming) re-edited it to their liking, proves that maybe the best director for subjects like racism in America is a non-American with an outsider's eye, showing brilliant intuition and objectivity with many black-and-white flashbacks and a grimy filmic language overall, along with a suitably WASP hard rock soundtrack. David McKenna's screenplay may seem filled with obscene, uneducated dialogue but that's why it's accurate because these are mostly meant to be trashy, working-class characters, and they are explosively played. Norton, who was nominated for a Best Actor Oscar, has never been better as he takes Derek from a take-no-prisoners white supremacist to an embodiment of desperation and remorse. Not to be outdone are Keach in a role for which none other than Marlon Brando was considered, and Beverly D'Angelo (yes, the wife and mum from the Vacation series) as his and Danny's unstable and guilty mother Doris. Also noteworthy are Kaye's sharp cinematography and Jerry Greenberg's and Alan Heim's relentless editing.

For all its on-set and post-production strife, as a story of a dysfunctional family and particularly two estranged brothers, a commentary on race in late-20th-century America or, perhaps most profoundly, a questioning of how deep regret and redemption can truly go, American History X very firmly makes its mark.

An album's accompaniment.

When the rock era arrived with the likes of Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley et al from about 1955, music had a brand new target audience (teenagers) who were starved for more than just the songs. Of course, to this day those are the meat in the sandwich, but when an album is truly, fully memorable, that's because it's stuffed to the gills with creativity and freshness. One of the added bonuses of LPs since then has been what you experience first each time: the cover art.

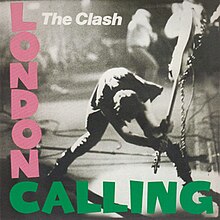

Photographer William Robertson created, in 1955, what has been called the first groundbreaking album sleeve, for Elvis' eponymous debut. The Clash deliberately echoed it for their 1979 release London Calling:

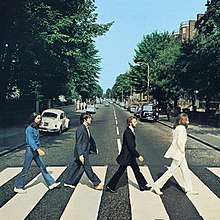

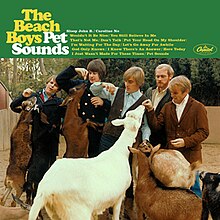

Swinging into the '60s (pun intended), the Beatles perfected the album sleeve and solidified its cultural appeal with their globally recognised creations for Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (the crowd on which remains run through with a fine tooth comb) and Abbey Road, while the designs for Bob Dylan's Blonde on Blonde and the Beach Boys' Pet Sounds also became famous.

The '70s then saw the height of the singer-songwriter movement (Elton John, Cat Stevens (who actually did his own art), Bruce Springsteen, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Randy Newman et al) and these performers arguably inspired their decade's most effective sleeve designs. It also brought Fleetwood Mac's Rumours and Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon which, while I hate that album, I can't deny the brilliance of its artwork.

And then there's for me the cover art to end them all: Tony Warren and Jim/Jan's superbly vivid and fitting orange, black and white swirl for Stevie Wonder's 1976 masterpiece Songs in the Key of Life. I could get happily lost in this design (and the album); it's such a shame Stevie's never been able to see it.

Entering the 1980s, cover art designs became more photography-based but this in no way impeded their effect. Indeed, many of the decade's blockbusters employed nothing else, from Michael Jackson playing with a tiger cub on the reverse of the Thriller gatefold to Madonna sitting up in bed on her Like a Virgin disc to Bruce Springsteen doing what controversially appeared to be pissing on the American flag for Annie Leibowitz's shot for the Born in the U.S.A. cover.

The '90s arrived musically with the image of a baby in a swimming pool reaching for a dollar bill. That LP was, of course, Nirvana's Nevermind, and though several other gems sprang from the last decade of the 20th century, like the Red Hot Chili Peppers' Blood Sugar Sex Magik and Green Day's Dookie, none of those had as much staying power.

Now, into the 21st century as music production and sales have become more digital, we've seen many fewer sleeves become famous in their own right, but cover art is still produced and often a key factor in how LPs are marketed. (Maybe some of this century's sleeves just need more time anyway.) And I must admit, most of the albums I've discussed here are by artists whose music I love but objectively, I can still appreciate album sleeves on some level even if I dislike the songs. Good designs set and suit the tone for what you're about to hear. Brilliant ones assume a life and legacy of their own. And collectively, they've formed a strong art form of their own and united two others even more.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)