On Thursday, I watched Edward Scissorhands for literally about the thousandth time. Naturally I already could've recited it in my sleep, and I chose to rewatch it then to mark receiving a T-shirt featuring it (which I obviously wore in the process). Even so, and I still can't quite establish why, I wasn't prepared for how much more it affected me this time. It's always made me cry, and in two scenes, but after this viewing I was also deeply angry. I ended up standing in my kitchen doorway, reflecting on some of my own unpleasant childhood experiences for a few minutes before making a post in a Facebook group about unabashedly angry films. Because that was my sudden realisation: despite primarily being a romantic fantasy, there's also a certain empathetic rage just coursing through it as Tim Burton made the protagonist semi-autobiographical.

Anyway, I don't love it any less now (I never will), but that was an out-of-body experience for me and it's left me contemplating how, and how often or rarely, we see something new in something very old or familiar, and what that observation can mean for how we perceive the thing overall. Or, for that matter, whether we really let ourselves change our perceptions enough. But I shouldn't even pretend to know the answers to those conundrums; I often don't even know how my brain works, never mind others' brains.

The closest answer I feel I can leave you with here is this: neuroplasticity is evidently real, and certainly regarding artistic interpretation.

Thursday, 30 July 2020

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #199: Wolf Children (2012).

Hana is a young university student in Tokyo with a pretty ordinary life. That is, until she meets and falls for a mysterious new male student. After they first meet, Hana learns he can shapeshift into a wolf but this does nothing to put her off him. In time they have two children: elder daughter Yuki, and younger son Ame. Their family life is going wonderfully, until the man is accidentally while scavenging for food. Now the widowed Hana chooses to move to the country where she is left with two half-human, half-wolf kids she doesn't know how to raise and who (like most siblings) frequently fight, and ultimately find their loyalties pulling them in very different directions.

Director and co-writer Mamoru Hosoda, who previously made 2009's Summer Wars and later 2018's Oscar-nominated Mirai (both also superb), is unquestionably one of the best animation filmmakers working today, and Wolf Children is him at the top of his game. He invests this deliberately metaphorical yet relatable narrative with the same familial message he would express even more overtly and successfully in Mirai, but this film stands on its own by simultaneously exploring the contemporary and traditional sides of Japanese life, through Yuki's and Ame's character arcs.

Visually, of course, it's mouth-watering, with painstaking attention to detail and continuity, and Masakatsu Takagi's music and Shigeru Nishiyima's editing both also enhance the consistency and emotional impact. The only fault I found with it is with one of the English-language version's vocal performances; Micah Solosud, at 22, sounds just far too old as the preteen Ame. But despite that minor drawback, these Wolf Children are a delightful pack.

Saturday, 25 July 2020

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #198: The Boys (1998).

After serving a gaol sentence for assault, Brett Sprague (David Wenham) returns home to his mother Sandra (Lynette Curran), brothers Glenn and Stevie (John Polson and Anthony Hayes) and his girlfriend Michelle (Toni Collette). They're in Sydney but below the poverty line, and Brett's explosive temper won't help that. Over this one day which Brett drinks his way through, he cunningly regains his status as man of the house one altercation at a time. This power struggle gradually unites the Sprague boys united in fury at their mother and girlfriends, culminating in their decision to hit the town that night and commit a despicable crime, the aftermath of which is revealed via flashforwards.

Based on Gordon Graham's play, which used the infamous 1986 murder of Sydney nurse and beauty pageant winner Anita Cobby as its main influence, this Aussie crime drama won four 1998 AFI Awards, including one for director Rowan Woods. It's very much a slow burn; until about the last 30 minutes all the action is dialogue-driven. But despite the sometimes excessive exposition, The Boys does convey a sense of confident, intimate suspense to the end. Stephen Sewell's script gives each character suitable and realistic dialogue while it lucidly shifts the focus back and forth between the present and the future, and experimental jazz trio the Necks offer an ominous but subtle score. But the real meat in this sandwich is surely the acting. All the performances are solid, but Wenham and especially Curran (both reprising their roles from the stage production) are absolutely ferocious in their roles.

If you like non-stop action in your crime dramas, look elsewhere. But if you're after one that offers a patient look into the events and acts that cause criminal ones, and then blows the lid off the pot, The Boys delivers.

Saturday, 18 July 2020

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #197: Song of the Sea (2014).

On an island in Ireland lives Conor (Brendan Gleeson), a lighthouse keeper and his pregnant wife Bronagh (Lisa Hannigan), with their toddler son Ben (David Brawle). All is well, until Bronagh gives birth and then mysteriously vanishes that same night into the ocean, leaving Conor, Ben and newborn daughter Saoirse behind. Fast forward six years, and Conor is emotionally destitute, Saoirse is a mute, and Ben is sullen and blames her for their mother's disappearance. Then, on Saoirse's birthday, their strict grandmother (Fionnula Flanagan) visits them, despite thinking they shouldn't be raised in a lighthouse. That night, after Ben scares Saoirse with the Irish legend of Mac Lir and his mother Macha, who stole his feelings and turned him to stone, Saoirse is revealed to be a selkie: a human who can shapeshift into a seal. Shortly after this discovery, on Halloween Ben and Saoirse inadvertently embark on a journey to a fantastical land which way hold the secrets behind their mother's disappearance.

This Irish-Belgian Oscar-nominated co-production initially enchanted me, but became rather like chewing gum: it lost its flavour quite soon for me. It is breathtakingly animated, but narratively I found it increasingly by-the-numbers and even shallow. That's both because of how I feel it was told, and how many family films I've seen - and loved - earlier which also explore themes of ancestry and mythology (like Coco, Where the Wild Things Are and The Red Turtle), so maybe had I seen this before all those it would've done what those others did for me, but in seeing it afterwards it ultimately just felt hackneyed for me. I also feel it had room for some humour and especially a classical Irish score, both of which director Tomm Moore and screenwriter Will Collins forewent. Song of the Sea deserves praise for bringing Celtic mythology to a mainstream audience, but hopefully the next movie to cover that fascinating subject will do so with more depth, distinctiveness and charm. 6/10.

Friday, 10 July 2020

I have a personal beef with a footballer. Reader discretion is advised.

This is Manly Sea Eagles prop Addin Fonua-Blake, and I don't care what race he is; he's a fucking arsehole. Why? Well, you should read what he said that made referee Grant Atkins send him off the field during a game last Sunday: he called Atkins a "fucking retard." On Monday he publicly apologised to Atkins for that. Now, I'd believe that apology was sincere, except it turns out that after the match, Fonua-Blake encountered Atkins and remarked: "Are your eyes fucking painted on, you bunch of spastics?" (https://www.smh.com.au/sport/nrl/fonua-blake-called-referee-a-spastic-during-second-spray-20200707-p559pn.html) Then in a video Manly released the next day, he said he didn't know how offensive those terms were. As if that's a fucking excuse or explanation.

As you all know, I have a neurodevelopmental disability and I follow the NRL quite closely, so these revolting comments immediately enraged me. For them, Fonua-Blake has been ordered to pay $20 000

and perform volunteer work with disability groups, which is music to my ears. But I somehow doubt that will make him learn his lesson, because he was already initially suspended for two games for contrary conduct (https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-07-10/nrl-fines-addin-fonua-blake-20000-dollars-for-abuse-of-referee/12443436) and in 2015 he was fired from the St. George Illawarra Dragons for assaulting a girlfriend https://www.dailytelegraph.com.au/sport/nrl/teams/dragons/dragons-have-sacked-addin-fonuablake-after-he-was-charged-with-common-assault/news-story/874ec8cb95d66a9c3abf2608b53a5891). What a saint, huh?

He may be a good footballer, but Addin Fonua-Blake needs to try (pun intended) much harder to be a decent human being.

He may be a good footballer, but Addin Fonua-Blake needs to try (pun intended) much harder to be a decent human being.

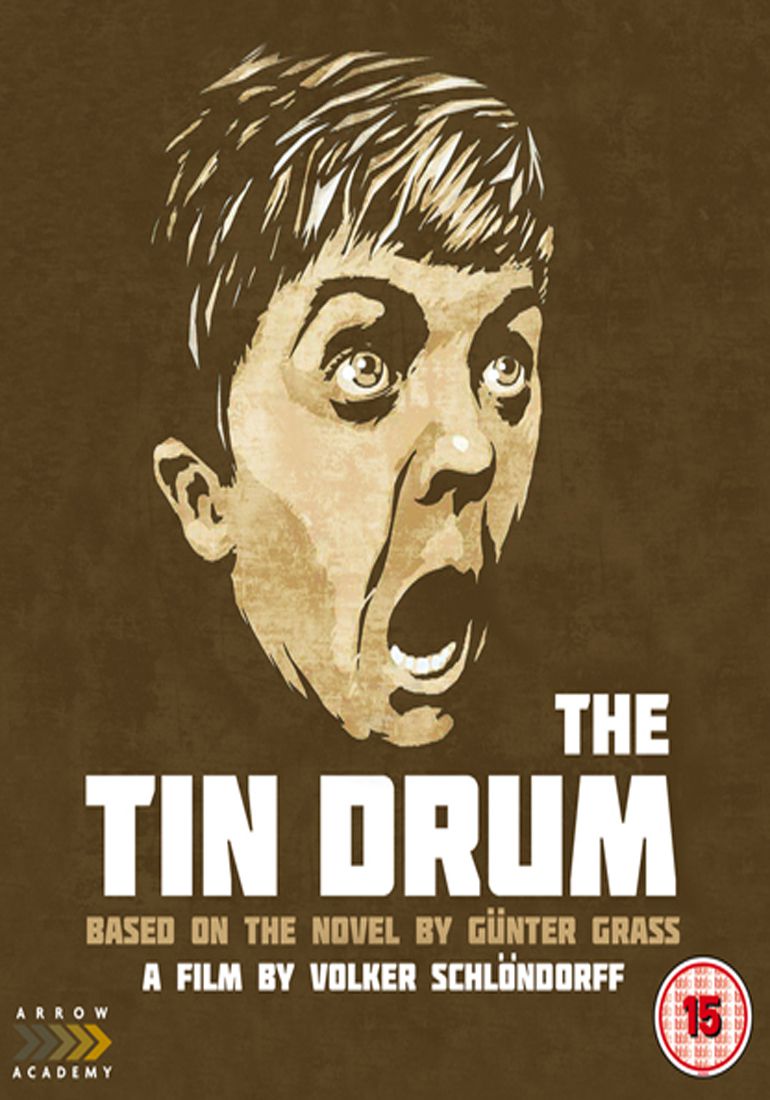

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #196: The Tin Drum (1979).

In this adaptation of Gunter Grass' celebrated 1959 novel, Oskar (David Bennent) is an unusual German boy on the sidelines of history. Born in 1924, at age three he suddenly stops physically growing and is given a tin drum for his birthday, from which he refuses to be parted. Around this time Oskar also discovers he has a scream which can shatter glass, employing it now whenever he's upset. Living with his single mother Agnes (Angela Winkler), who's unsure as to the identity of Oskar's father, until she dies with no explanation, Oskar now finds himself taking a rather picaresque journey around Germany under the newly-elected Third Reich, encountering such experiences as joyful as sex and music, and as horrible as war.

Volker Schlondorff's The Tin Drum won both the 1979 Best Foreign Language Film Oscar and the Cannes Film Festival Palme d'Or, and deservedly so. This is a sprawling, whimsical, graphic and strange but ultimately deeply powerful and measured examination of Nazi Germany and coming of age. Schlondorff's direction is admirably objective and lucid, bravely but discreetly withholding nothing in the sexual and violent scenes and cohesively weaving the magic realist elements into the rest of this tapestry, and his screenplay with Jean-Claude Carrire and Franz Seitz adequately reflects the era's mood and lingo. Bennent, in a challenging role for a child actor, makes Oskar a layered and charmingly mischievous but relatable young hero, but the best performance comes from Winkler, who turns what could've been simply a browbeaten single mother into a woman with clear backbone and dignity.

Some other pluses are Maurice Jarre's majestic score, the strikingly authentic period design, and the vibrant editing and cinematography. All in all, it's no wonder The Tin Drum was, well, a big hit.

Some other pluses are Maurice Jarre's majestic score, the strikingly authentic period design, and the vibrant editing and cinematography. All in all, it's no wonder The Tin Drum was, well, a big hit.

Friday, 3 July 2020

Something Cult, Foreign-Language or Indie #195: The Breadwinner (2017).

11-year-old Parvana (Saara Chaudry) lives in war-torn Kabul, Afghanistan under Taliban rule with her widowed mother Fatema (Laara Sadiq), her elder sister Saraya (Shaista Latif) and baby brother Zaki, whom she frequently regales with fantastical stories. Her elder brother Sulayman (Noorin Gulamgaus) has been killed in the conflict and her father Nurullah (Ali Badshah) has been wrongfully imprisoned following a misunderstanding with volatile young Taliban member Idrees (Gulamgaus again), leaving Parvana's family without an adult male relative. This means they're unable to support themselves as women and girls are banned from going outside. Therefore after one failed attempt to do just that, Parvana tries to do so again, this time disguised as a boy, her "nephew" Aatish, to find help for her and her family. This ploy works, scoring her food and money, so naturally she continues it, taking a quest to free her father from his prison, with the help of Shauzia (Soma Bhatia), another girl disguising herself as a boy, whom Parvana meets en route.

Based on Deborah Ellis' 2000 novel of the same name, the 2017 Best Animated Feature Oscar nominee The Breadwinner is a stunningly insightful, sympathetic and respectful depiction of Afghani, especially Afghani female, life under the Taliban, brought to life with a striking aesthetic that feels like a traditional and stop-motion animation hybrid, with a vivid colour and detail scheme to boot. Irish animation director Nora Twomey, working with Ellis' and Anita Doron's screenplay and even Angelina Jolie as an executive producer, approaches this very delicate and culturally specific narrative with complete objectivity, curiosity and patience, all the while keeping a firm grip on the animation's continuity and flow without lacking a sense of playfulness where appropriate (particularly in the storytime scenes which, come to think it, add another enjoyable narrative layer themselves). Enhancing all this are Sheldon Lisoy's photography, Garragh Byrne's editing and particularly Jeff and Mychael Danna's score.

It's maybe not as moving as it could, or should, have been, but then again it's a family film seeking to explore a very delicate and topical subject. Nonetheless, The Breadwinner achieves that balancing act and also proved quite thought-provoking for me. I should also salute Netflix and Universal Pictures, to US companies, for being willing to distribute a film about this subject. The Breadwinner is, well, a winner.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)